Although the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Democratic Union Party (PYD) are ideologically affiliated, they remain organizationally distinct. Even though it does not pose a direct security threat to Turkey, the PYD’s increasing consolidation of power in northern Syria arguably poses a challenge not only to Ankara but also to the PKK.

BACKGROUND: During the 1980s and 1990s, the Syrian government allowed the PKK to establish bases and training camps in Syria and the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon. Although they accounted for only a small proportion of the total, Syrian Kurds also fought in the ranks of the PKK. In October 1998, under pressure from Turkey, Syria expelled PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan from Damascus and forced the organization to relocate its camps and bases to the Qandil Mountains of northern Iraq. Over the next decade, the Syrian regime also began to clamp down on its own Kurdish minority, particularly after simmering ethnic tensions erupted into anti-government protests in the northeastern city of Qamishli in March 2004.

In June 2004, the PKK returned to violence after a five-year ceasefire. Fehman Huseyin, a Syrian national also known as Dr. Bahoz Erdal, was appointed head of the PKK’s military wing, the People’s Defense Forces (HPG). In 2009, Huseyin was replaced as head of the HPG by another Syrian national and former PKK field commander, Nurettin Halef al Muhammed, who used the nom de guerre of Sofi Nurettin. Other Syrian Kurds continued to join and fight for the PKK although they probably never accounted for more than around ten percent of the total.

The PYD was established in 2003 by Syrian Kurds sympathetic to the PKK. In 2004, Iranian Kurds established the Party of Free Life of Kurdistan (PJAK). The formation of separate Syrian and Iranian parties coincided with a major shift in Öcalan’s ideology. Öcalan had founded the PKK in 1978 as an explicitly Marxist party. Through the 2000s, under the influence of the writings of the American libertarian Murray Bookchin, Öcalan had begun to advocate a form of communalism and the creation of a highly decentralized “democratic confederalism”, characterized by a large degree of local autonomy. In theory, what Öcalan termed the Group of Communities in Kurdistan (KCK) would be based on a pyramidal structure of representative committees and assemblies, starting at street and village level and culminating in an assembly and executive committee. It would transcend current international borders and incorporate not only Kurds but also other communities in the region. In theory, rather than one of them asserting precedence over the other, the PKK, PYD and PJAK would be separate and equal parts of the KCK.

Until the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, the PYD was an underground organization with very limited military capabilities. The situation changed in summer 2012 when Syrian President Bashar al-Assad withdrew the majority of his forces from predominantly Kurdish areas in northern Syria in order to concentrate them against rebel groups in the rest of the country. With the de facto connivance of the central government, the PYD started to fill the vacuum by asserting its own authority over the area.

The PYD’s limited military capabilities meant that in some areas its own members were reinforced by PKK units. But, through 2012 and into 2013, there were sometimes tensions. Some Syrian Kurds complained about what they termed the arrogance of the PKK members and their tendency to treat them as subordinates. It was not uncommon for PYD and PKK members to harass each other as they passed through the other’s checkpoints.

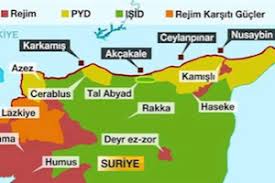

IMPLICATIONS: In July 2013, the PKK reorganized its high command. Murat Karayılan, a Turkish Kurd and a veteran field commander, took over as head of the HPG. Karayılan’s appointment was accompanied by an increasing “Turkification” of the PKK as many Syrian members returned to Syria to assist the PYD. In November 2013, the PYD announced that it had established three autonomous – and, at the time, non-contiguous – cantons in northern Syria which were known collectively as Rojava.

Through late 2012 and into 2013, the PYD’s own nascent militia – known as the People’s Protection Units (YPG) – had been mainly responsible for what amounted to policing duties. However, the offensive launched by what became known as the Islamic State in late 2013 – and particularly in 2014 when it made deep inroads into Kurdish areas in northern Syria – meant that the YPG had to transform itself into a military force capable of confronting the Islamic State on the battlefield. The transformation was led by Syrian Kurds who had acquired combat experience in the PKK, but was also supplemented by the transfer of Turkish Kurds from the PKK to the YPG. Almost all of the YPG’s units are now commanded by PKK veterans. In effect, experienced PKK fighters – whether Turkish or Syrian nationals – provide the skeleton for the YPG, which is fleshed out by recruits from the Kurdish community in Syria, and in a reversal of the process before the Syrian civil war, young Kurdish volunteers from Turkey. No reliable figures are available, but Turkish Kurds are currently estimated to account for up to forty percent of the YPG.

The expansion and transformation of the YPG occurred at a time when the PKK was observing a unilateral ceasefire in Turkey, which was first announced in March 2013 following the launch in late 2012 of direct talks between the Turkish state and Öcalan, who has been imprisoned in Turkey since 1999. From the PKK’s perspective, its deployments in Syria were an opportunity both to further Öcalan’s ideological goals by consolidating the implementation of his theoretical model in Rojava and to enhance the organization’s international reputation by combating the so-called Islamic State.

However, the deployments also meant that the PKK was reluctant to return to a fully-fledged insurgency even after President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan unilaterally abrogated the talks with Öcalan in March 2015. Although the organization did eventually return to violence in summer 2015 – initially by sanctioning the murder of two policemen in retaliation for perceived Turkish involvement in a suicide bombing that killed thirty-three Kurdish and leftist sympathizers in the Turkish border town of Suruç in July 2015, and then in retaliation for the massive air raids against PKK positions in northern Iraq ordered by Erdoğan in response to the murders of two policemen – events in Syria have resulted in changes in the PKK’s strategy.

The PKK is aware that any diversion of resources from Syria to Turkey would leave it vulnerable to accusations that it was abandoning the Syrian Kurds to the predations of IS. But its deployments in Syria have inevitably reduced the number of militants available for its insurgency inside Turkey. As a result, although it has continued to stage occasional attacks on military outposts, the main focus of the PKK insurgency has now shifted to the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), either delivered by vehicle or planted along roads used by the Turkish security forces. In addition, since August 2015, the PKK has – for the first time in its history – launched a concerted campaign to assert its authority over urban areas in southeast Turkey. The forces deployed by the PKK in the cities, which are known as the Civil Defense Units (YPS), consist of a small number of trained militants – including some who gained experience of urban warfare from fighting against ISIS during the 2014-15 siege of Kobani – who are supplemented by a larger number of young, mostly relatively untrained, volunteers. In theory, the PKK’s urban campaign is designed to detach certain areas from the authority of the central government in Ankara and implement at the local level Öcalan’s theory of “democratic confederalism”.

CONCLUSIONS: Since early 2015, the PYD has greatly expanded the territory under its control, including linking two of its three cantons, and is now threatening to create a contiguous strip of territory along most of Syria’s border with Turkey. It has also made considerable progress in terms of creating an alternative administrative structure in Rojava based on Öcalan’s writings.

The Turkish government frequently insists that Rojava poses a security threat to Turkey, even disingenuously claiming that the YPG has fired artillery shells across the border. In reality, the PYD has no interest in antagonizing Turkey and no incentive to give Ankara an excuse to target it militarily. From a self-centered perspective, the PYD has much more to gain – both politically and economically – from a cordial relationship with Turkey than from a hostile one. Nor can Rojava be used as a platform for the PKK insurgency in Turkey. Most of the border between Turkey and Rojava runs through flat and open terrain, which is relatively easy to secure. Even when Syria was actively supporting the PKK in the 1980s and 1990s, militants would still mainly infiltrate across the considerably more mountainous border between Turkey and Iraq rather than directly from Syria.

The large number of its former and current militants that are deployed in the war against ISIS means that the PKK can currently exercise considerable influence in the YPG. However, the various administrative structures that have been established in Rojava are highly indigenized, and almost exclusively staffed by Syrian nationals with no direct organizational links to the PKK. If the military situation in Syria stabilizes, there is likely to be a shift in focus – and thus also in influence – away from the YPG to the civilian administration.

On March 17, 2016, the PYD announced the creation of an autonomous body in Rojava called the Federation of Northern Syria. Although the announcement failed to gain international traction, it is difficult to see how any permanent solution to the Syrian conflict can be achieved without at least some form of devolution. As it continues to put down roots in Rojava, the PYD currently appears well placed to consolidate its position as the main force in predominantly Kurdish areas.

But it is probably here, rather than in any direct security threat, that the main challenge to Ankara lies. Any decline in the fighting in Syria would free up more PKK militants for its insurgency in Turkey. Arguably more critical would be the psychological impact. The consolidation of a Kurdish entity in Syria would inspire Turkey’s own already increasingly alienated Kurds to push even harder for some form of autonomy. In the PKK leadership in Qandil, the feelings would probably be mixed. Despite their theoretical equality, the PKK has always regarded the PYD as a subordinate. As a result, any satisfaction at the PYD’s consolidation of power in northern Syria would likely be muted by the awareness that the PKK itself has yet to achieve the same success inside Turkey.

Gareth H. Jenkins is a Nonresident Senior Fellow with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program Joint Center.