By Karwan Faidhi Dri, republished from Rudaw.

In the early hours of a May morning, a drone dropped a bomb on Turkey’s Diyarbakir airport. It was an audacious attack by a band of armed Kurdish fighters who have been fighting the Turkish state from the mountains for decades, using mostly AK-47s, and is part of an evolution of warfare that has left even the United States army almost powerless to stop these flying birds near its bases across Iraq.

Gerila TV, a website linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), has published 10 videos of PKK drone attacks against Turkish soldiers in 2021. The videos open with a shot of the PKK’s yellow and green flag with a red star in the middle waving in the air high above the ground, attached to a hexacopter that is carrying three bombs.

None appear to have caused casualties, but the increase in drone attacks this year signals a new military tactic in its conflict with the Turkish state. It’s a development that could help the PKK on the battlefield, but has its limitations, according to experts.

The PKK began its armed struggle in the eighties when a group of Kurds picked up rifles. As they grew, they established bigger camps in the mountains and acquired larger weapons like rocket propelled grenades (RPGs), BKC machine guns, and materials for roadside bombs.

However, Turkey’s developments in the field of drone technology in recent years means the PKK also had to change tactics.

The PKK’s interest in drones began in 2007 after Turkey began using the unmanned aerial vehicles for surveillance, according to a former PKK fighter who fought with them for nearly two decades.

Murat Karayilan, a member of the PKK’s executive body, “obtained a model helicopter in 2009,” the former fighter told Rudaw English on condition of anonymity. “I was working with him at the time. He asked an expert from Europe to develop its capacity in order to fly it as far as six kilometers and drop bombs.”

The first published report of the PKK looking into drone technology was on February 4, 2016 in Ajans Haber, a pro-government news outlet in Turkey, which said the PKK was trying to use drones that could be controlled from 200 to 300 meters away and could carry up to 1,000 kilograms, a figure that seems exaggerated.

The claims in the article could not be independently verified, but the first known instance of the PKK using drones was in August 2017 when it deployed an off-the-shelf drone carrying explosives against a Turkish military base near Semdinli, wounding two soldiers.

Nearly four years later, the PKK announced on May 25 that it had carried out 34 drone attacks against the Turkish army since Ankara launched two military campaigns in Kurdistan Region’s Duhok province on April 23. The drones targeted Turkish forces in both the Kurdistan Region and inside Turkey, including attacks on two military bases in Batman and Sirnak and one against Diyarbakir’s 8th Jet Base. These are key bases the Turkish army uses to launch air attacks against the PKK.

Turkey has made enormous strides in its own drone program. Domestically-made drones entered the Turkish army’s inventory in 2014. The PKK claimed it downed a Turkish drone on July 17, 2016.

In the last few years, Turkey has extensively used drones to attack the PKK, to deadly effect especially when targeting the group’s top commanders in the Kurdistan Region and areas disputed by Erbil and Baghdad. The death of Zaki Shingali, top commander of PKK forces in Shingal, in a drone attack was alarming for the PKK.

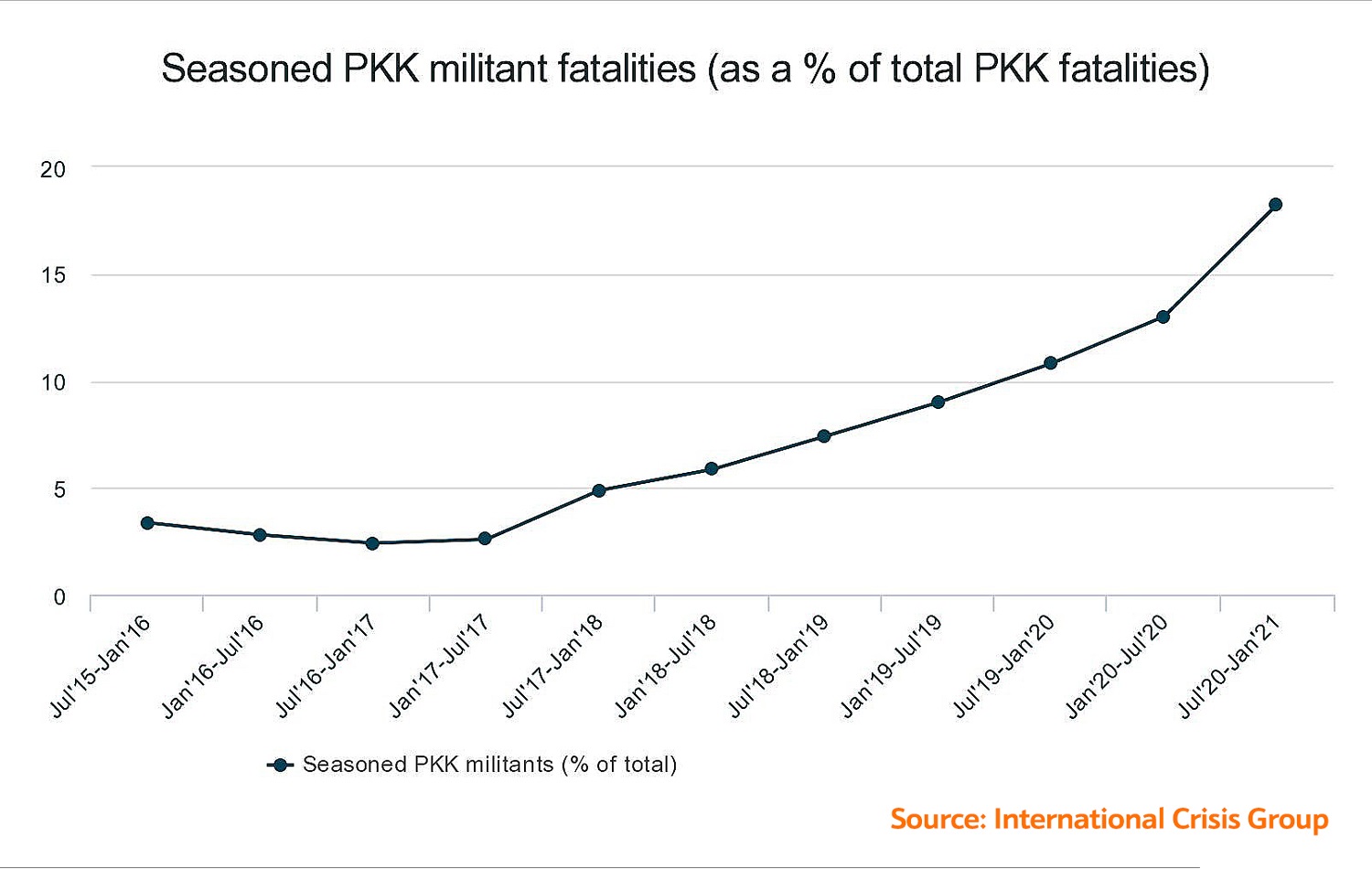

The International Crisis Group, which tracks the PKK-Turkey conflict, has documented a dramatic increase in casualties among the PKK’s leadership since 2017, likely due to Turkey’s drone power.

Why drones?

“Since Turkey demonstrated it had the capability to assassinate senior PKK members with air and drone attacks with the unprecedented assassination of Zaki Shingali in Sinjar [Shingal] back in August 2018 I think the PKK has sought to develop some capability to strike strategically-important targets in Turkey,” Paul Iddon, a freelance journalist who writes about Middle East affairs, told Rudaw English.

The increased attacks against the PKK inside the Kurdistan Region and the “unprecedented assassination campaign most likely propelled the PKK to try and develop the means to be able to retaliate,” Iddon added.

Turkey’s operations against the PKK inside its own borders are mostly carried out by forces on the ground, but it relies heavily on drones and jets when attacking the group’s bases in the Kurdistan Region.

Alex Almeida is a private sector security analyst. He told Rudaw English that the PKK’s aim in developing drone capabilities is “primarily showing off and trying to harass Turkish forces without losing any of their own fighters.”

“The cheap, commercially-available drones the PKK is using are most effective when employed together in large numbers, like ISIS [Islamic State group] did in Mosul in 2017 or for precision strikes against infrastructure sites and other small vulnerable targets,” added the analyst.

“So far we’ve seen the PKK primarily use drones against Turkish combat outposts and other positions in the northern Kurdistan Region, but only in small one-off attacks using one or two drones dropping munitions or diving into their targets. These attacks are mostly an irritant for Turkey and haven’t been very effective, though there are signs the PKK are further developing their drone tactics,” Almeida said.

The videos shared by Gerila TV do not show the drones causing extensive damage or casualties. Some fall in areas where no soldier or military base can be clearly seen.

Cemil Bayik, a top PKK commander, acknowledged to Responsible Statecraft on April 15 that Turkey’s development of high-tech arms has definitely “created some problems for us. But we are developing the type of guerrilla organization and struggle which can render such high-tech weapons null and void.”

He added they are developing “measures and military concepts” to confront Turkey’s sophisticated weapons technology, including drones, and claimed their “new guerilla tactics and measures” caused Turkey’s military February operation on Mount Gara to fail, though he did not elaborate. Turkey launched an operation on February 10 to rescue 12 Turkish citizens held by the PKK. It ended the operation a few days later when the 12 were found dead.

The PKK’s Karayilan said in August 2019 that they were trying to “modernize and professionalize” PKK fighters so that they are “capable of prevailing over the enemy’s intelligence and techniques.”

“Developing drones is probably part of this effort, but their ability to develop anything more sophisticated than commercially available DJI-type drones rigged with explosives has yet to be seen,” said Iddon, adding the drones used by the PKK in attacks against military bases inside Turkey in late May were “very basic and primitive.”

The PKK will try to develop their drone capabilities, but “whether or not they can is, of course, another question,” he added.

Almeida says the PKK – whose armed struggle is mostly carried out in mountainous areas – does not have indigenous drone manufacturing capability, adding “they are limited by what kinds of commercially-available, off the shelf drones they can acquire and modify.”

“There are some larger commercially-available fixed-wing drones that have longer range and can carry a heavier payload than the small drones we’ve seen the PKK employ so far. It’s possible they may try to use these in the future, if they haven’t already. For example, the recent drone attack on Diyarbakir air base in Turkey was almost certainly staged using heavier fixed-wing drones,” Almeida said.

Murat Yesiltas, a researcher at the pro-Ankara SETA think tank, said in an article on May 22 that the PKK’s drone attack “seems to have not reached their targets so far. But it is very clear that it points to a new development that should not be taken lightly.”

Sourcing the drones

Although the drones can be easily found in the market, it is not clear how they end up in the hands of the PKK in mountainous areas. Bringing them across the border from Turkey is not a viable option. In the Kurdistan Region’s Duhok and Erbil provinces, tensions are high between the PKK and the ruling Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), limiting the PKK’s ability to move around. Only in Sulaimani province does the PKK have freedom of movement, but even here they are under Turkish air surveillance.

Rudaw English reached out to PKK-affiliated sources about their drone program, but they declined to comment.

Yesiltas claims the PKK established a “drone academy” in Makhmour Camp in Erbil province. The camp is administered and secured by the PKK and has been bombed by Turkey. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan claimed on Sunday they killed the head of the camp, who he identified as Selman Bozkir. State media also claimed on Friday that Turkish intelligence operatives killed Hasan Adir, who allegedly co-administered the camp with Bozkir, in a separate operation.

The Turkish analyst said the PKK’s drone development was given a boost by international support for another Kurdish armed force across the border, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), who are an American ally in the war against ISIS.

“It is clear that the weapons and training given to the YPG in Syria in recent years have had an effect on the PKK, increasing its financial capacity. Especially the ‘drone academy’ located in Makhmour has been transformed into a production center to develop the PKK’s air attack capacity,” Yesiltas wrote.

Turkish officials have repeatedly asserted that weapons given to the YPG by the US-led global coalition against ISIS end up in the hands of the PKK – an allegation denied by the YPG’s political arm, Democratic Unity Party (PYD). Claiming the YPG is a Syrian offshoot of the PKK, Ankara has called on the US to end its support for the Kurdish force.

The PKK is suspected of enjoying close relations with Turkish regional foes like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and possibly Iran. Could these allies provide the PKK with sophisticated drones? Both Almeida and Iddon think this is unlikely.

“No, this is very unlikely. Also, larger and more advanced (i.e. dedicated military-type) drones also require dedicated launching systems (some of them vehicle-mounted) or even airstrips, which the PKK wouldn’t be able to operate effectively or doesn’t have access to,” said Almeida. But, “the PKK could still do plenty of damage with some of the more high-end drones that can be purchased commercially,” he added.

Iddon “seriously” doubts that anyone is supplying the drones or their parts to the PKK, saying “all the parts used in these drones are available commercially, anyone can buy them.”

Turkey’s pro-government Hurriyet news outlet claimed that in the attack on Diyarbakir air base, a part of the drone that is used to hide the unit from radar, was imported from Canada.

Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar said on May 3, “Unfortunately, some countries that we know as friends, gave missiles to the PKK. Therefore, each of them is a great danger, a great risk for us.”