By Karwan Faidhi Dri

A young woman wanted to get to know someone whose account she had spotted on the social networking app Instagram. She typed out a simple hello in Turkish, “Merheba,” and pressed send; she would have to wait and see if 28-year-old Jutyar Muhsin replied or not.

The message from Nadia Fadi, accompanied by her profile photo selfie, caught Jutyar’s attention, and the two start to exchange messages. Typing in different languages and scripts, they struggled to understand each other, but they got by.

After messaging each other on Instagram and speaking on the phone for ten days, the two finally agreed to go on a date someplace quiet, to avoid prying eyes. Nadia made Jutyar dot around until he arrived at the final destination – a quiet, picturesque spot in Duhok’s Chamanke subdistrict, where snow lined everything in sight. As the taxi moved through the last checkpoint run by the Peshmerga before his destination, Jutyar must have had first date jitters.

The car came to a sudden halt in front of a group of Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) fighters blocking their way.

“The taxi driver’s mobile was taken from him and the tyres of his taxi made flat by PKK fighters to prevent him from asking for help,” said Jutyar’s father Muhsin, citing the driver who later gave testimony to local security forces.

Jutyar was abducted on January 29, 2020, never to see his family again.

Nadia claimed to work at Vajeen Hospital in the city of Duhok. Instead, she was a member of the PKK and Jutyar her prey, Muhsin said.

“She had promised she would marry him and my son did not know that she was a member of the PKK,” Muhsin said. Rudaw English contacted Vajeen Hospital’s administration, who said that they had no doctor called Nadia Fadi on record.

It had been two days since anyone had heard from Jutyar when Muhsin received a phone call from an unfamiliar number. The woman on the other end of the line spoke in the Kurmanji dialect of Kurdish. Her accent suggested she was from the province of Sirnak, just across the Iraq-Turkey border, Muhsin recalled, but she was using a number from Korek, the most popular telecom company in the Kurdistan Region. It was the same woman who had introduced herself to Jutyar as Dr. Nadia Fadi.

“She said, ‘I have been waiting for him for a couple of days. I have wanted to speak with him but he has been out of reach.’ I told her that he followed her instructions and disappeared, and that she knew where he was. She said she did not know,” said Muhsin. She told him that she was from Sirnak but worked as a doctor at Vajeen Hospital, a few kilometers away from the house Jutyar and his family lived in.

Muhsin did his best to convince Nadia to meet somewhere, but she kept saying “I cannot” without explaining why. When he asked her if he could meet her at the hospital she had said she worked at, she ended the call. Jutyar’s father tried for several days to call her back, but to no avail.

Jutyar was not the only one fooled by Nadia’s advances. Rudaw English has learned from several of Jutyar’s friends and acquaintances, who did not want to be named, that she had approached other young men too. Jutyar’s fate served as a cautionary tale, and the men became more wary of who they were speaking to.

Muhsin is a member of the KDP, which controls most of Duhok province. He asked his party to use their communication channels with the PKK to find out what happened to his son, but the KDP said it could not get any information on Jutyar’s circumstances or whereabouts.

News from Jutyar

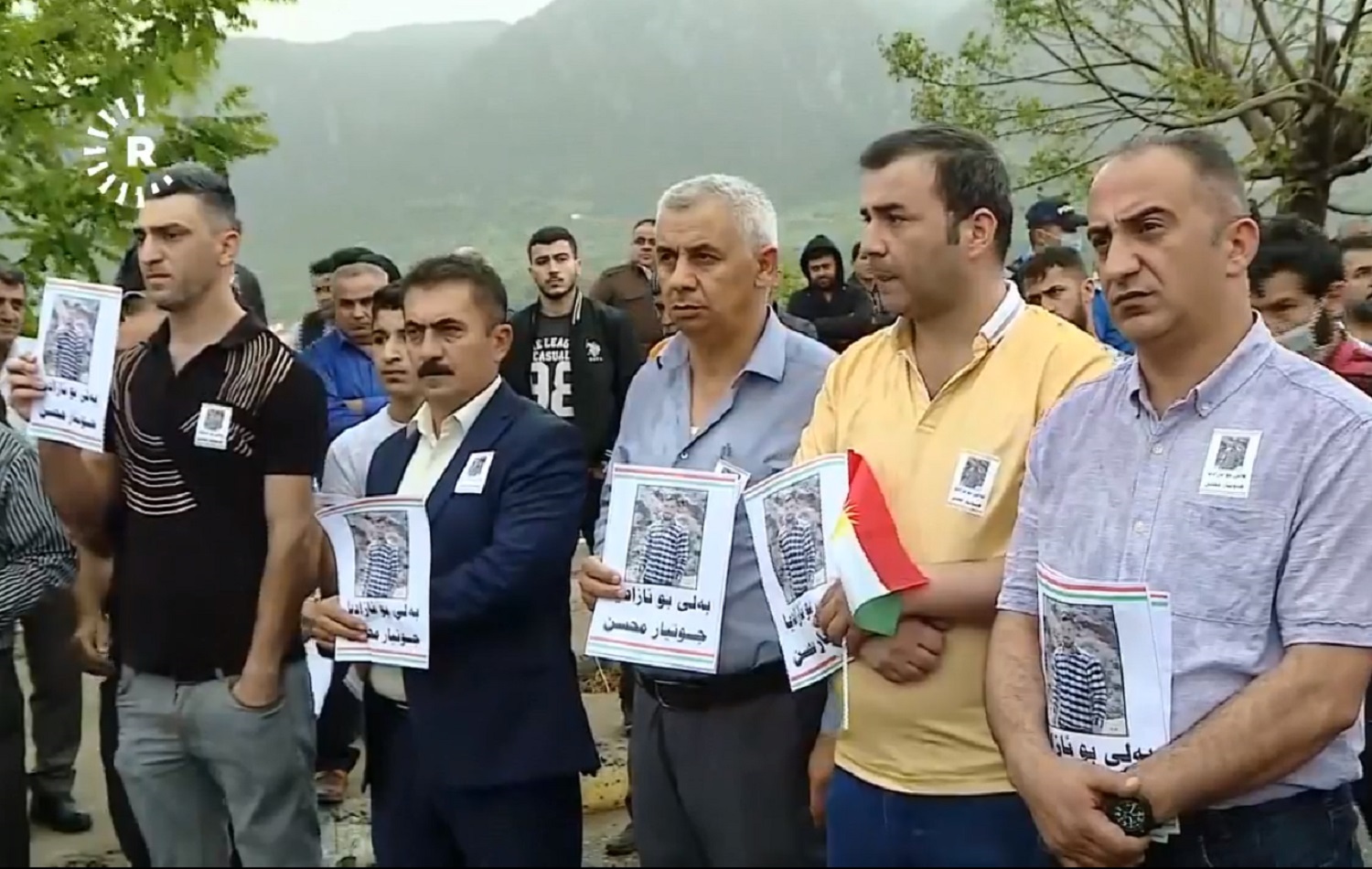

Jutyar’s exasperated family held a protest in Duhok on May 5, calling on the PKK to release their son.

Three days later, the PKK sent a video of Jutyar to his family through the PKK-KDP communication channels. Jutyar says in the beginning of the 55-second video that it was recorded on May 2.

“I am staying with the Hevals,” Jutyar says in the video Rudaw English was given access to. Heval is a Kurdish word the PKK uses to mean comrade. “I am well, and I have not been harmed at all. The Hevals are very good with me,” Jutyar says in the video.

Jutyar asks his family not to worry about him, and says he is talking to the PKK to reach a deal, without giving details. The video ends with Jutyar wishing viewers a happy Ramadan.

As Jutyar’s family hoped the awareness raised by the protest would lead to good news about him, the PKK released a video of him purportedly confessing that he was a spy for Turkey.

“A person named Jutyar Muhsin has been arrested by our forces for espionage and passing on the coordinates of the guerrillas’ locations, which led to the bombing of [PKK-held] places by Turkish fighter jets,” the PKK said in a statement released by its affiliated media outlets.

The PKK indirectly accused the KDP of organizing the protest against Jutyar’s abduction because several officials from the party attended the event. It said that “those who buy weak people like Jutyar Muhsin for a few pennies and thereby sully their hands with the blood of the guerrillas are distorting the facts by organizing rallies later on in this context.”

The KDP and PKK have had thorny relations for decades. The KDP has enjoyed economic relations with Ankara through the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). KDP officials have often called on the PKK to leave the Kurdistan Region. Turkey has also established dozens of military bases in KDP-controlled territory, and interior minister Suleyman Soylu said on Friday that it would be establishing another base soon.

In the confession video, Jutyar’s hair looked freshly cut and he was clean shaven. He seemed less happy than in his previous message.

Jutyar says in the video that he provided Turkey with the coordinates of PKK positions in the area. However, his father said that Jutyar, who left school when he was in the eighth grade “did not even know how to spy.” Jutyar was not a well-spoken person, Muhsin said, but he spoke eloquently in the hostage videos. He suspected that Jutyar’s captors trained and forced him to make the confession.

For guerilla groups like the PKK, hostage taking can be an effective trump card against a military powerhouse like Turkey.

“We know from the history of this decades old conflict that the PKK has at times resorted to abduction tactics and used individuals it abducted as cards attempting to elicit concessions on the battleground from Turkish security forces,” said Berkay Mandiraci, Turkey analyst at International Crisis Group.

The abduction of civilians in the Kurdistan Region by the PKK is rare. However, two Ukrainian civilians were held hostage in Duhok province for over three years until December 2020 because of a botched arms deal. The office of the mayor of Chamanke sub-district, from where Jutyar was taken away by the group’s militants, said there have been no abductions from the area since 2015 – making what happened to Jutyar all the more confusing.

When Shivan Jalal, Jutyar’s cousin, was asked why Jutyar was abducted by the PKK, he said that there were several reasons, but that it was most likely because they were a family well known in Duhok for refusing to assist the PKK. Another possible reason is that most of Jutyar’s relatives are Peshmerga fighters affiliated with the KDP, Shivan said.

Turkey launched the aerial and ground Operation Claw-Eagle 2 against the PKK on Mount Gara, Duhok province on February 10, lasting for four days. Three Turkish soldiers, including two commanders, were killed in the first two days of the offensive, according to the Turkish defense ministry. The PKK claimed that the number of Turkish casualties was higher.

However, news from the Turkish defense ministry of the deaths of 12 people – the number later changed to 13 – appeared to affect the course of Claw-Eagle 2, which came to a quick end two days later. News of the deaths made local and international headlines, and the US Embassy in Ankara said on February 12 that they were “saddened by the killing of Turkish soldiers by PKK terrorists.” However, the US Department of State released a statement two days later, condemning the deaths of the Turkish citizens “if reports of the death of Turkish civilians at the hands of the PKK, a designated terrorist organization, are confirmed.”

Some Turkish officials claimed that the aim of Operation Claw-Eagle 2 was to rescue the 13 hostages, so it naturally ended after their deaths. It was later confirmed that 12 of the hostages were members of the Turkish security forces, captured over the course of the last six years, and the thirteenth an Iraqi civilian. The PKK said in a statement released on February 17 that the Iraqi civilian was Jutyar, and that all 13 people were killed by Turkish bombardment of Siyare Prison camp on Mount Gara, where they were being held.

Upon hearing the news about Jutyar’s death, Rudaw English contacted his father for comment. He refused to believe the news. He said that Rudaw English was the first person to break the news to him. Muhsin asked for evidence about his son’s death so Rudaw English sent him the Kurdish version of the statement from the PKK. He began crying, although he was still not wholly convinced that his son was dead, because he said that the PKK had promised to release him soon. “How can I break the news to his mother?” he asked.

A man from Zakho’s son was missing; he suspected that his son had been abducted by the PKK. He went to Turkey to see if the “foreign individual” killed during the operation was his son, but it was not; he returned with no answer. Muhsin heard about the man, contacted him, and showed him old photographs of his son. The man who had seen a body other than his son’s at a morgue in Turkey’s Antalya province told Muhsin that Jutyar was the dead man he saw in Turkey. For Muhsin, it was a strong indicator that his son really was dead.

“We hired a taxi and headed to Malatya [in Turkey] on the night of February 21 and arrived there the next day,” Muhsin told Rudaw English. He said that the Turkish authorities were “very helpful,” accompanying Muhsin until he was done with paperwork and logistics.

Malatya Governor Aydin Barus accompanied the family for most of the trip, and even organized a helicopter, which took the family and their dead son’s body from Malatya to Silopi, on the Turkey-Iraq border. Before Muhsin left Turkey, a DNA test was done to confirm it was Jutyar’s body, then it was washed as per Islamic rituals at a mosque, according to Muhsin.

Jutyar’s body arrived in Duhok on February 23 and was buried at a local cemetery after an autopsy was conducted.

Who killed Jutyar?

Both the PKK and Ankara accuse each other of killing Jutyar and the other 12 hostages at Siyare, and an independent fact-finding investigation into the incident – as requested by the PKK – is too dangerous to carry out.

The PKK has claimed several times that the 13 hostages were killed by Turkish bombardment, despite their efforts to protect them. Murat Karayilan, a senior commander of the PKK, said in an interview with the PKK-affiliated Sterk TV on February 22 that they treat hostages as guests.

“We see hostages as guests and act in accordance with this [principle]. Those people who ordered the Operation [Claw-Eagle 2] are to be held responsible for the deaths of the hostages,” said Karayilan, naming Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Defense Minister Hulusi Akar. “If there was law in Turkey, these people would resign and be tried.”

Karayilan, whose PKK had previously accused Jutyar of espionage, said they treated him as one of them and did not put him in the jail where the 12 Turkish people were held. He even called Jutyar a Heval.

“One of our Hevals, Jutyar, was also there, the Hevals making preparations to release him. Actually, he was living with the Hevals. He was not living among them [the Turkish hostages]. He was from us. We were responsible for [protecting] his life but when it comes to his death Turkish authorities are to be held accountable.”

The PKK said 15 of their fighters were killed in the four days of clashes, including six prison guards at Siyare.

PKK-affiliated media released videos of the aftermath of the operation on the mountain. In the videos, the PKK fighters claimed that Turkey used chemical gas in the attack.

“They used gas. The prisoners here have been killed by the gas and the bombardment. They have been executed so that the blame could be put on us,” claimed a fighter, introduced in the video as Hogir Med.

Muhsin said that when he saw his son’s dead body at the morgue in Malatya, there were no signs of damage to the body except a hole in his head. He said that the autopsies carried out on Jutyar’s body in Matalya and Duhok concluded that there were no signs of death by chemical gas inhalation. Rudaw English asked to see a copy of the autopsy report, but Muhsin refused, saying local officials asked him not to share it. Rudaw English was allowed to see the photograph of Jutyar’s dead body. The hole in his head cannot be seen clearly. Jutyar’s eyes were black, blue and swollen.

The PKK sent a condolence letter to Jutyar’s family on February 16, saying again that Turkey killed Jutyar. Rudaw English obtained a copy of it from Jutyar’s family.

“The Turkish fascist state used poisonous and chemical gas after they could not enter the camp because of the resistance from Hevals,” read the letter, attributed to General Command of Gare, signed with an initial, R.

“Jutyar was with us for some time. He lived in a different place than the one where the hostages of Turkish fascist state were staying. He lived among the Hevals and was receiving training. We had decided to release him during Newroz celebrations. Hevals were making preparations for this, but he was poisoned and killed during attack by the Turkish fascist state. Our Hevals resisting inside the camp were martyred too.”

The letter asked the family to collect their son’s dead body from the Turkish government.

The PKK has not elaborated on why Jutyar – who was initially introduced as a spy – was receiving training from the PKK and lived among them rather than in the prison and what sort of training he was receiving. Rudaw English could not reach any PKK sources for comment on what happened to Jutyar. Rudaw English reached out to Mohammed Penjwini, a Kurdish writer, veteran politician and friend of PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan for comment on what happened to Jutyar. “I don’t know anything about it and there is no need to talk about it.”

Turkey’s defense minister claimed that the PKK killed the 13 hostages “when the air operation began.”

“The cave entrances were fortified with iron gates. It was not possible for our air force’s bombs to reach the area … Only tear gas was used. Several calls were made for the terrorists to surrender,” Akar said when briefing Turkish parliament on February 16. The minister claimed that the head of the prison, who was among the PKK casualties, had ordered the shooting of the 13 hostages, citing two PKK fighters who were later captured and interrogated by the Turkish army. Akar had previously claimed that the PKK had shot the 13 hostages – one in the shoulder, and the rest in their heads.

Turkish defense ministry released the “confessions” of the two PKK fighters. Servan Korkmaz and Merkaz Botan, who were allegedly guarding the prison, said that they killed the hostages as per directions from their boss who had previously ordered them to kill the hostages if Turkey attacks and they do not get backup from PKK.

Duhok Governor Ali Tatar’s office said in a statement on February 23 that they condemned the “abduction, capture, imprisonment and martyrdom of Jutyar Muhsin Siyari – son of Duhok province – by the PKK fighters,” and said that only judicial authorities of the area can capture, not the PKK.