Regardless of whether the warlords on both sides ignite a new fire on this reconciliation, a turning point has occurred for Kurdish civil society

Houshang Sheikhi

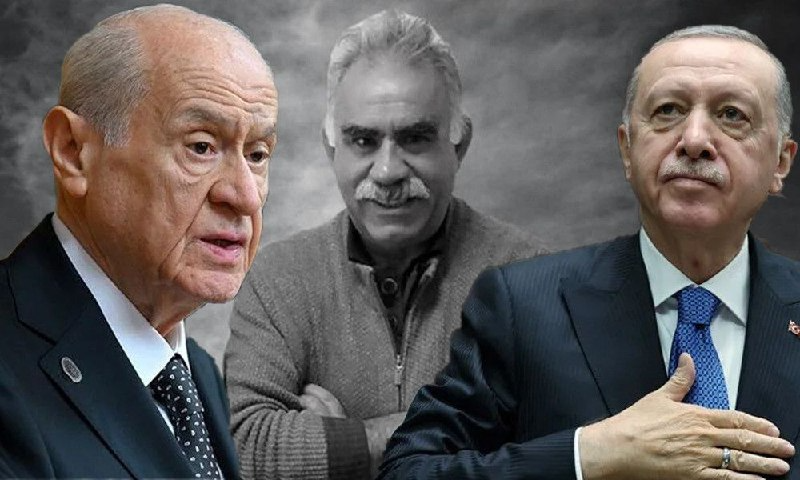

Abdullah Öcalan’s message, the imprisoned leader of the PKK, regarding the necessity of disarmament and the dissolution of the group—beyond the specific aspects related to Turkey and the fate of the conflict between the PKK and Turkey, and the consequences of the Kurdish identity dispute in Turkey—carries another fundamental point that requires analysis and examination. The fact that the leader of a Kurdish movement, after 40 years of armed struggle, has now concluded that the contemporary era no longer tolerates Kalashnikovs and guerrillas demands deeper reflection. The movement he established in 1978 and ordered to take up arms six years later is now, after four decades and the deaths of over 150,000 people from both sides, being called for dissolution in a handwritten message by him.

Although, theoretically, there is no place for armed struggle in the manifesto Öcalan has elaborated over the past two decades based on the life of democratic societies, this announcement has logically been made at least 20 years late. This is because, according to the core ideas of Öcalan’s texts, he underwent fundamental theoretical transformations after his arrest in a joint operation by MIT, Mossad, and the CIA at Kenya’s airport in 1999. In his texts, he focused more on the democratization of societies, considering it a prerequisite for the democratization of states, and distanced himself from early Apoist socialism, focusing on a specific type of communitarian philosophy, in which armed struggle naturally has no place.

Therefore, it can be said that weapons, both as a tactic and as a strategy, are fundamentally at odds with such a manifesto. Öcalan’s disarmament and dissolution of the PKK, before being an agreement between Öcalan and the Turkish government, is an attempt to resolve the existential crisis of the Imrali prisoner’s philosophy. Regardless of whether Qandil pays heed to Imrali’s words, what has happened is a significant and important development for Kurds throughout the region. It is natural that those who have defined armed struggle not as a tactic or even a strategy, but as part of their identity, now face not only strategic confusion and ideological frustration but also an identity crisis.

Therefore, in addition to the critical analyses and opinions of PKK supporters regarding Öcalan’s deviation from all his former Kurdish ideas, some artists, who have expanded symbolism and romanticism in Kurdish movements, especially the PKK, have joined the wave of criticism against him. For example, Nizamettin Ariç, a singer and painter, depicted a distorted image of Apo in two neo-expressionist paintings and started the “Goodbye Abdullah Öcalan” campaign, which was continued by the Kurdish writer Jan Dost, who also criticized Öcalan in the same symbolic and romantic style that the PKK had used to criticize others for years.

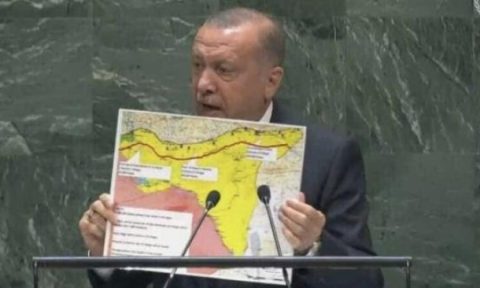

Despite all these media outcries, it should not be overlooked that Öcalan’s public announcement in 2025 did not happen suddenly, as his theoretical developments have been evident to all observers of Kurdish issues. From 2002 to 2014, messages with content similar to the recent message were published by him. Consequently, it was the 2012 message that sparked the reconciliation process in Turkey, and the following year, Masoud Barzani and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, along with Ibrahim Tatlises and Şivan Perwer, took the stage in Diyarbakir, heralding peace between Kurds and Turks in Turkey. However, with the start of the trench wars in several Kurdish cities in Turkey at the end of 2015 and the deaths of over 15,000 people from both sides, there was no hope for peace.

Regardless of whether the warlords on both sides ignite a new fire on this reconciliation, a turning point has occurred for Kurdish civil society. Moreover, when Öcalan, through his call for the dissolution and disarmament of the PKK, announces the end of his various ideas of self-governance, autonomy, federalism, confederalism, and independence, it means that, in addition to the impasse in armed tactics or strategy, the futility of the destructive ideas that have plagued Kurdish regions for many years is also declared. Although the PKK’s condition of Öcalan’s physical presence at the PKK congress and Turkey’s refusal have cast doubt on the fate of this agreement, the months-long negotiations between Hakan Fidan and Ibrahim Kalin with Öcalan, the agreement reached, and finally, the assignment of the initial proposal to Devlet Bahçeli, one of the heads of Turkey’s hard power core, indicate Ankara’s planning for various levels of the PKK issue, which also includes Turkey’s southern neighbor.

This is because Mazloum Abdi’s signing of a surrender letter to Julani to merge into Julani’s organization, despite the clear contradictions between his 53-article constitution and the 8-article Abdi-Julani agreement, is in line with Öcalan’s disarmament call and the new path taken by the PKK and its affiliates. However, Kurdish groups, which generally lack up-to-date strategies and have followed a similar path for the past hundred years, despite the fundamental differences in the political, social, and cultural issues of Kurds in different cities and countries, have also institutionalized a kind of anachronism and political romanticism resulting from the movements of others around the world, which has always plunged Kurdish societies into a fruitless turmoil and imposed many victims on these politicized societies for an unclear and non-political path.

This approach has also led to the romantic symbolism overshadowing the social and political life of these people due to the analytical errors of their elites, instead of thinking, rethinking, and prioritizing the improvement of the Kurdish people’s lives. Instead of focusing on results and facilitating a good life for the Kurdish people, it prefers failed heroes to realist politicians and stereotypically generalizes the dichotomies of traitor-servant and collaborator-patriot to the entire society, attempting to exclude those who are not obedient from the circle of Kurdishness.

However, this is the first time that, at the height of an armed Kurdish group’s activity, its leader has made an explicit call for abandoning weapons. The last time a Kurdish leader said that nothing could be achieved through guerrilla warfare was the late Mullah Mustafa Barzani, who, in despair following the 1975 Algiers Agreement, announced the end of his career and became known in contemporary Kurdish history as “Ash-e Batal,” meaning an empty mill. “Ash-e Batal” is derived from a term in the worldview of the people of Kurdistan. In the old days, when the miller’s wheat ran out, he would shout from the top of the mill that the mill was empty, so that people would bring their wheat to his mill. This time, however, the miller of the Turkish Kurds, not due to tactical or strategic limitations similar to the 1975 Iraqi Kurds, but based on historical experience and to escape a discursive contradiction and an anachronism that he himself mentioned in his handwritten message, has called for disarmament and dissolution. This time, the call is not for pouring wheat into his mill, but for dismantling the mill.

It is essential to note that, firstly, this call has been made to all groups formed by the PKK and its subsidiaries, and naturally, PJAK is also included, and this group, if it considers itself a follower of Apo’s philosophy, must also dissolve and disarm. Secondly, this call has crucial aspects for other Kurdish groups and is an opportunity for them to reconsider and break free from the existential, structural, and functional crises among other armed Kurdish groups. However, if disobedience occurs by the PKK and its affiliates after Öcalan’s call, and the path is blocked by various conditions, and the ideological foundations are not revised, and Qandil insists on a failed experience, in addition to the possibility of escalating conflicts on the borders of Turkey with Iraq and Syria, the division in Turkish Kurdish society will also deepen.

This is because moving beyond Öcalan and the arrival of the era of Kalkan, Bayik, Karasu, and the like could lead to the intensification of Kurdish political romanticism, which has so far resulted in the tragic deaths of hundreds of thousands of people in this region, and its continuation will be a comic confrontation between Kalashnikovs and hypersonic missiles. Öcalan’s call is an opportunity not only for the PKK and its affiliates like PJAK but also for weaker Kurdish groups in the region, such as the three branches of Komala, Democrat, PAK, and others, to fundamentally revise a fruitless path that has led to the waste of opportunities and becoming proxies for others, and to free themselves from the existential crisis. By adopting the principles of political realism and distancing themselves from Kurdish romanticism, they can, by understanding the context and time and abandoning anachronistic concepts, tactics, and strategies, take a rational and courageous step to correct a century of misdirection, which could result in the development of the lives of the people they claim to be fighting for. Otherwise, the process of these groups becoming proxy actors for regional and international rivalries and conflicts will intensify, resulting in costs for the people they claim to be fighting for. Therefore, self-criticism, rethinking, and revising goals, aspirations, and tools in line with realism are the only rational path for Kurdish movements, groups, and parties to free themselves from various crises and pave the way for them to align with the times and context.